Invocation:

I call upon the Many-tongued mimic. Teach me how to weave my orphan-tongue in a loving blanket around the song of the tale, to shuffle the riffs and uphold the integrity of a well-worn image. To let the beings who are coming, and those that are long-gone speak from the cavern of my beak, prophecy and eulogy all at once. Let my imagination, and my mouth be not a museum but a strange swirling dream. Where the culturally orphaned, and the stories that dreamt in the hills and valleys of my ancestral homes can dance switching partners to the pulse of the faerie-music.

Tellings Tales with the Tongues of Birds

As a Euro-descended speaker of english in North America I often struggle to find the ways that my language is deeply rooted in the land, where is the language of the wind in the willows, the sloth prowl of the bob-cat, or the blush of the spring storm at dawn tuning the lilt of my words when I use this colonial tongue? The stories struggle to bubble up directly out of the landscape through the untended wounds that live in the earth, and in the soil of my family's ancestral heritage. All the stories, both monsterous and magical, that were obscured, occluded, thrown away gather in heaps like cairns marked on maps that I can only in my dreams. The autochthonous tale feeling inaccessible, I often feel like a mimic, a parody, a tape recorder playing back dreams from some other time separated from me by a veil.

As we waited for the arrival earth-side of our son, I took once again to a well-loved practice of sitting and watching the yard unfold into spring. Everyday, like a touch stone in the midst of the storm of the initiation of it all, I went to the yard to sit and watch and offer something of beauty to the unfolding. The Wrens nested in their usual haunts, their songs and lightning chirps exploding from the hidden zones, Robins visited in waves of red flowing across the sky, and the Cedar-wax wings filled the air with high pitch feedback. One day the radio-dial turn song of the Northern Mockingbird picked up, and all spring did not stop. More and more of my attention was courted by this Mockingbird, and his eventual mate. They dance their hopping courtship dance, and made their nest in the very heart of the soon to be flowering roses. A heart-home wreathed in a crown of white blossoms.

Mimus polyglottos, the many tongued mimic, danced and sung their way deeper and deeper into the temple of my attention. Teaching me more in a season about my aspirations for fatherhood than any baby-book. When I first heard his latin name uttered, it was a spell-casting. The many-tongued mimic. As a settler on stolen land, as a person whose families have buried their first languages in the debris pile of English, as a storyteller endeavoring to court the hidden gods and monsters of my ancestral people. As a mixed-up, mashed-up tapestry of strange weaving, the many-tongued mimic a perfect name. I started to behold the bardic nature of this bird, the way they played with riffs in the ecology adding in the calls of the migratory birds as the season deepened, not only a mimic but a herald calling out the names of the visiting heroes from the great jet-streams. The deeply prophetic accuracy of the timing of it all, calling out to the Robin before they arrived, a summoning.

The Weight of Fate and the Blood of Dragons

Sigurd was born after the death of his father, raised in the halls of his murderers. A life haunted by this loss, but shot-through with care, a nest of sharp sticks and gold thread. King Hjalprek did his best to be kind to Sigurd, and his mother Hjordis wrapped her mantle of motherly love around him. As he grew, and his boyish clay called out for molding he was sent to live with the iron-cunning dwarf Regin for fostering. In the forest Regin taught the boy skill, game, and magic:

Runes of wisdom then Regin taught him,

and weapons’ wielding,

works of mastery; the language of lands,

lore of kingship, wise words he spake in the wood’s fastness.

Regin, a mottled mentor, teaching true wisdom and bending Sigurd towards dark purpose, pushes him to demand a horse from his step-father. It is freely given, and in the walk to secret pastures Sigurd is met by a long-bearded grey wanderer. He takes him to a herd of horses, who they chase them from the wildflower meadow in the wood into the fast flowing waters. The grey-beard tells him to pick the horse that stays longest in the torrent. Grani he is named, descendant of Odinn’s eight-legged steed Sleipnir and the greatest among horses. There is ancestral magic here, Sigurd’s family name Volsung comes from Volsi an ancestor’s name, but also a cognate for a treasure of the family; a preserved horse phallus sacred to the horse god Freyr.

Then Regin convinces Sigurd to kill the dragon Fafnir and promises to forge him a sword to do so. Reginn is a master-smith and forges sword after sword for the young Sigurd who breaks each and everyone one by dashing it on the anvil. It is not until Sigurd retrieves the shards of his father’s sword Gram (we can see Tolkien's inspiration for Narsil and Anduril) to be re-forged that Reginn is successful in forging a sword for him. The finest sword, the only tool that will fit in our hands must be forged from that which was broken by those before us. The ancestral gifts that fill our accompany us as we head on the quest of soul-making, in Sigurd’s case to meet dragons.

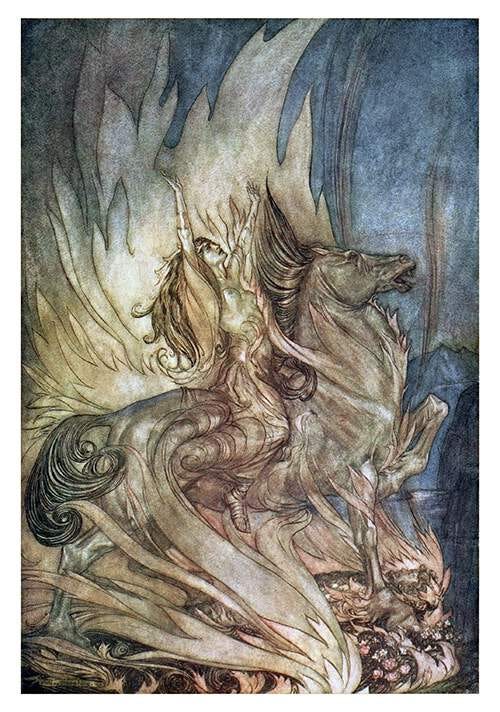

Girded with the sword of his Ancestors, and riding the fylgja of his line Sigurd journey’s into the dream of his life to meet the terror-beast Fafnir. Once again he is met by the grey-beard in the woods who advises him to dig several pits, hiding within and stabbing Fafnir in the heart with his sharp sword Gram.

As the dragon’s blood spills, across the landscape reddening Sigurd up to his shoulders the two speak, of wisdom, fate, prophecy. Fafnir counsels Sigurd:

“I advise you, Sigurth:

Take my advice,

and ride home from here.

My clanging gold,

this ember-glowing weather,

will bring about your death.”

The gold is cursed, ancestrally for transgressions of the gods against the family of Fafnir. Sigurd does not heed this doom-saying but instead cuts out the dragon's heart and brings it back to Regin. Regin begins to cook the heart over the open coals, and tells Sigurd to watch it for him. And like young Fionn cooking the salmon of knowledge for his mentor Sigurd dutifully does so, watching as the meat cooks and the blood begins to boil. He reaches in to check the readiness of the magical morsel and is burned. He soothes his finger and when blood hits tongue, riding on the burned finger, he is cracked open. The languages of many lands, lores of kingship, the wisdom spoken in woods sprouts feathers and takes wing. Suddenly the meaning of the birds lilting song comes flooding into young Sigurd:

“There sits Sigurth,

splattered with blood,

cooking Fafnir’s heart

on the open flame.

I would say this prince

was a wise man,

if he were the one who ate

the dragon’s heart.”

“Over there is Regin,

conspiring against Sigurth,

he’ll betray this boy

who trusts him.

In his bloody rage,

he ponders evil –

that wrongdoer

will avenge his brother.”

“I would think Sigurth was wise

if he knew how to heed

your good advice,

my sisters,

if he took our advice

and set a table for the ravens.

I always suspect a wolf

when I see a wolf’s ears sticking up.”

In their knowing, the birds speak to Sigurd of the unseen cunning and evil intention of Regin who sits plotting out of sit. Under the auspices of the bird-knowing Sigurd takes the life of his twisted-mentor, who was indeed plotting his death and is sent towards his destiny.

Listening to the Language of the Birds

According to Dr. Jackson Crawford the birds that speak of the impending peril to Sigurd are the white wagtails. Wagtails are a long-tailed bird native to western europe, and cousins in coloring and size to my dear from mimus polyglottos. Dr. Crawford makes this species identification by noting that the word in Old Norse used for the birds is igthur, which is similar to the name for the white wagtails in several Norwegian dialects around the Salton Sea.

The language of the birds, Fionn mac Cumaill’s “music of what is,” is laden with weight of prophecy, warning, magic, and wonder. Learning to listen and speak with a feathered ear and tongue seems to have been an aspiration of magicians of many kinds throughout the millennia. The work of brontë velez and Weaving Earth has revealed to me that the word Auspicious comes from the old latin auspex, “one who ponders the flights of birds for omens.”

It is evident that these old stories are carrying traditional ecological practice and knowledge hidden within and behind these images of ecstatic oneness with place and its denizens are intimations of practices and life-ways that our pre-modern ancestors kept alive.

I first came into contact with the notion, and then practices of Bird Language through a mentor Dr. Paul Astin who on a rambling hike up some dry arroyo in Tongva Land (Topanga Canyon, California) put me onto the work of Jon Young, and suggested I find a copy of What the Robin Knows? This book details and distills decades of the practice of pattern awareness on the land, and gives easily accessible descriptions to several of the sentence structures and emotional inflections of the speech of the birds. I went from barely noticing the small balls of feathers flitting around the trails, fixated on the soaring Hawks and flapping Ravens to an obsessive seeker of the small peeps and chips of Bushtits, Chickadees, and Wrens. The world was alive with conversation, and I knew I was in it.

After years of study, particularly in the care of the Weaving Earth Center for Relational Education, the language started to unlock and unfold. Making daily romps to the same haunts in the woods to tuning into the fluting voices in all seasons the language of pattern, improvisation, and mystery continues to complexify. I have heard it said that bird language travels at nearly 2 miles a minute, that means two miles down the trail from where I am the birds are reporting in waves all the actions around me. The prophecy of my coming heralds me in a parade of feathered speech, and the same goes the other direction. To the auspex the voices of the birds herald the movements of the others out of sight, the low to the ground popcorn like alarm signaling the approaching bobcat, the quickly moving alarm calls in the canopy a Sharp-shinned hawk really catching the wind.

For a year I went every day to a sit spot, hidden behind an ash tree quite near a trail. I would sit for about an hour each day, and listen to the unfolding. At some point I started to tune in to the movements of the people on the trails, the different waves of sound that accompany a runner, someone busy on the phone, the speeding mountain biker. Indeed I started to pull out and became aware of myself noticing that the birds responded to the weight in my heart in much the same way. The learnings from this time on the land were stretched by the good questions, ponderings and musings of my community.

During this same time I was struggling heavily with depression, and often would come to my spot to be held with the sorrow. I began to notice that the birds, often Acorn Woodpeckers, on the trail to the spot reacted differently depending on the weight of my heart or the swirl of my mind. Moving further afield, with louder flutter of wings or alarm when the dark-ponderings would over take me staying closer in letting me know they knew it was me when I was cresting the wave of some buoyant moment. Like the igthur in the story they could hear and then report my feelings to all those listening in the forest, and let's be clear that is everyone. The fox, coyote, badger, snake, ash, oak, and willow all know in their way the language of the birds. The great unfolding pattern includes all of their meaning-filled gesture and response. My mind like Regin’s broadcast to the whole forest, in rippling waves of beautiful language.

To know the language of the birds, is to finally realize once and for all, that you are not alone but instead a singer in the beautiful symphony of what is.

References:

Crawford, Jackson. The Poetic Edda: Stories of the Norse Gods and Heroes. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2015.

Crawford, Jackson. The Saga of the Volsungs: With the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2017.

Shaw, Martin. A Branch from the Lightning Tree Ecstatic Myth and the Grace in Wildness. White Cloud Press, 2011.

Tolkien, J.R.R, and Christopher Tolkien. The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Resources:

Mindfulness and Bird Language Course

https://www.leadtolife.org/ - you can read more about brontë and their work here.

More of Chaise’s work can be found below at his website chaiselevy.com or on Patreon.

Thank you for this sharing! As a Canadian with roots in England Scotland and Germany and similar longings Chaise I hear you, I hear you. Blessings on your journey.